Walking Tour of Tempelhof Field: 7. Gravediggers in Neukölln

Deutsch

„This war separated husbands from their wives, and sons from their mothers, and I’m one of them, a seventeen year old boy forced to work in a foreign German country, in the middle of Europe, brought to Berlin, where work in the cemetery awaits me […] There is no hope of return.“((Wolfgang G. Krogel (Hg.), Bist du Bandit? Das Tagebuch des Zwangsarbeiters Wasyl Timofejewitsch Kudrenko, Berlin 2005.)) These are the first lines in a diary kept by Wasyl Kudrenko, a former inmate of the Protestant Church’s forced labor camp in Neukölln.

The Neukölln labor camp, which once stood where the plaque stands today, was run by the Protestant Church from 1942-1945. Most of the survivors interviewed after the fact say they were not aware at the time that the camp belonged to the Church. It was intentionally positioned on Hermannstrasse, a great distance away from the entrance to the cemetery. In doing so, wrote historian Heidemarie Oehm, the Church ensured that “the appearance and dignity of the cemetery could not be damaged.”((Heidemarie Oehm, Technokratische Effizienz. Organisation, Errichtung, Ausstattung und Betrieb des Neuköllner Friedhofslagers, in Erich Schuppan (Hg.), Sklave in euren Händen. Zwangsarbeit in Kirche und Diakonie Berlin-Brandenburg, Berlin 2003, p. 95-152)) The barracks stood in two parallel rows. The entire camp was surrounded by a barbed wire fence. In order to protect the barracks from air raids and keep them unidentifiable to passersby, they were painted with a green camouflage pattern.

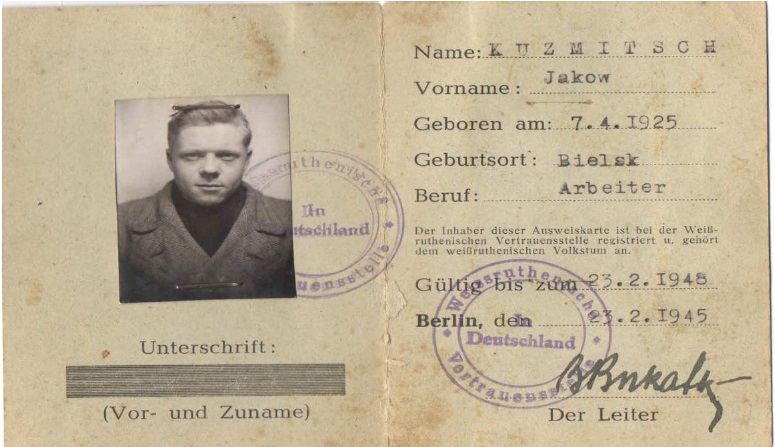

Gavil P. Tkalisch’s falsified identification card. He was born on April 7th, 1923 in the small Ukrainian city of Chernobyl and became a prisoner at the Protestant Church’s forced labor camp in Neukölln in 1942. He was able to escape the camp in 1943, and, with the help of a Russian who was legally living in Berlin, he obtained false documents that allowed him to legally work in Germany.

Source: Family archive of W. G. Tkalitsch

Approximately one hundred “Eastern workers” (Ostarbeiter), both men and women, were imprisoned here at the camp. Most of them came from Ukraine, and some from Russia. Each worker was provided a living space of approximately 3.5 square meters, in comparison to a German worker, who was provided 10 square meters. Every day, the prisoners went to several cemeteries throughout the city in order to dig graves. The “Eastern workers” were forced to wear a patch which read “Ost” (East) on the right side of their shirts, in order to distinguish them from the rest of the workers. The laborers were paid for their work, but living expenses were subtracted from their income, leaving them an amount which equaled less than a quarter of what the German workers earned.

The cemetery barracks were struck on multiple occasions by air raids. In April of 1944 the team barracks (Mannschaftbaracke) were burnt to the ground. Although a barrack was built in its place six months later, bombing raids destroyed the camp completely early the next year. During the final weeks of the war, the Allied forces continuously bombed the city, which as a result completely disrupted the supply of food. During the air raids, prisoners managed to escape and hide in the subway stations, in basements and in the sewers. In April of 1945, the Red Army liberated the Neukölln labor camp.

In the year 2000, fifty-five years after the conclusion of the war, the Church began to confront its war-time past. Thirty-nine Protestant and three Catholic churches took part in and/or ran labor camps in Berlin. In the 1990s, during a highly publicized debate in Germany concerning restitution for forced laborers, the Protestant Church publicly took responsibility for the injustices that it committed.

If you follow the path and continue across Hermannstrasse, you will reach another section of the St. Thomas cemetery (Hermannstrasse 179/185). There you will find a pavilion which houses a permanent exhibit (see map: P) featuring the stories of ten former forced laborers from Russia and Ukraine. The pavilion is open from April-October on Wednesdays and Sundays from 3:00pm to 6:00pm.

Ekaterina Akopyan

Read on

- Walking Tour Tempelhofer Feld (PDF for printing, in German)

- Wolfgang G. Krogel (Hg.), Bist du Bandit? Das Lagertagebuch des Zwangsarbeiters Wasyl Timofejewitsch Kudrenko, Berlin 2005.

- Mario Maturi: Erinnerungen 1943-1945